What is Critical Race Theory (CRT)?

To answer this question we need to begin by laying out a basic definition. Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, two well-known scholars of Critical Race Theory, provide a helpful definition in their book Critical Race Theory – An Introduction.

“The critical race theory (CRT) movement is a collection of activists and scholars engaged in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power. The movement considers many of the same issues that conventional civil rights and ethnic studies discourses take up but places them in a broader perspective that includes economics, history, setting, group and self- interest, and emotions and the unconscious. Unlike traditional civil rights discourse, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.” (CRT, 3)

Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw and co-authors offer further context in the intro to Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. They argue that early Critical Race Theorists tried to show “how law was a constitutive element of race itself: in other words, how law constructed race.” They argue a key task of Critical Race Theory today is to remind us “how deeply issues of racial ideology and power continue to matter in American life,” especially in the aftermath of what they call the “Age of Repudiation” in the 1990s, which marked the “rejection of the always fragile civil rights consensus and [the idea] that government not only can but must play an active role in identifying and eradicating racial injustice.” (CRT-KW xxv, xxxii)

As a method of analysis, Critical Race Theory helps us uncover the complex histories and power relations that underlie the construction of social categories like race, class, and gender via laws and social norms. We can then use this knowledge to critically evaluate and expose how power constructs specific forms of social relations. For example, when we say that race is “socially constructed,” what we mean is that the concept of race, what it means to be “white” or “Black” in the US, for example, has a distinct genealogy that we can trace to show how the very category of “race” as a social category came into existence and how views about race evolved over time (such as how the Irish or Jews became “white”). But to say that race is socially constructed is not to say that race is only an idea—because we know that ideas have real material consequences.

What Critical Race Theory as an analytic lens helps us to do is uncover how these expressions of social power operate, whose interests they serve, and how these dynamics can be changed. Critical Race Theory as a political movement tries to call our attention to and to help us see these issues clearly. So as Delgado and Stefancic note, CRT as both a method of scholarly analysis and a critical intellectual movement builds on these insights to bring about political change.

Roots of Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory as a distinct movement emerged in the 1980s from Critical Legal Studies (CLS), which was itself an earlier movement in the 1970s among legal scholars and practitioners which sought to question the supposed neutrality of the law. CLS drew on earlier insights from both the Legal Realism movement and European scholars affiliated with the Frankfurt School’s Institute for Social Research, which before the rise of Nazism in the 1930s included many German and Jewish philosophers and theorists whose gave birth to the field of Critical Theory. The genealogy of these intellectual movements is quite fascinating but is beyond the scope of my talk tonight. For those interested, there is a good overview of this history in the book Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement, edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Kendal Thomas.

Today there are thousands of scholars who draw on CRT, and their analysis has expanded beyond just law. Because CRT is a diverse approach embraced by different scholars it is difficult to provide a single, unified definition that everyone agrees on. But despite this diversity of CRT theorizing, there are some common threads that many CRT scholars would likely agree on, and which Delgado and Stefancic refer to as the “basic tenets.”

- First, racism is ordinary, rather than exceptional. It is business as usual in US society, and racism underlies everyday experiences for people of color and many immigrants. This ordinariness means that racism is difficult to address because it is not acknowledged.

- Second, the racial hierarchies created by white supremacy serves important purposes, both psychic and material, for the dominant group. In CRT literature this is often called “interest convergence” or “material determinism,” which argues that racism advances the interests of both white elites (materially) and working-class whites (psychically), creating disincentives for whites to challenge these racial hierarchies.

- Third, race is a “social construct.” The idea of race is a product of social thought and social relations, and not objective, biologically inherent, or fixed. Race is a category that society invents, manipulates, and retires as needed.

- Fourth, is paying attention to the effects of “differential racialization” and the ways that dominant society racializes different minority groups at different times in response to shifting social norms.

- Fifth, the concepts of intersectionality and anti-essentialism, which recognize that each race has its own origins and ever-evolving history, and no person has a single, easily stated, unitary identity. How these identities overlap or intersect is always in flux.

- Sixth, the idea that communities of color bring a distinct voice and lived experience to discussions about race that whites lack. As Delgado and Stefancic note, this idea exists in an uneasy tension with notions of anti-essentialism, but this idea is an important part of the growing “legal storytelling” movement within CRT circles.

This is obviously a very cursory review of some basic ideas that one might encounter while studying Critical Race Theory.

What CRT Is Not

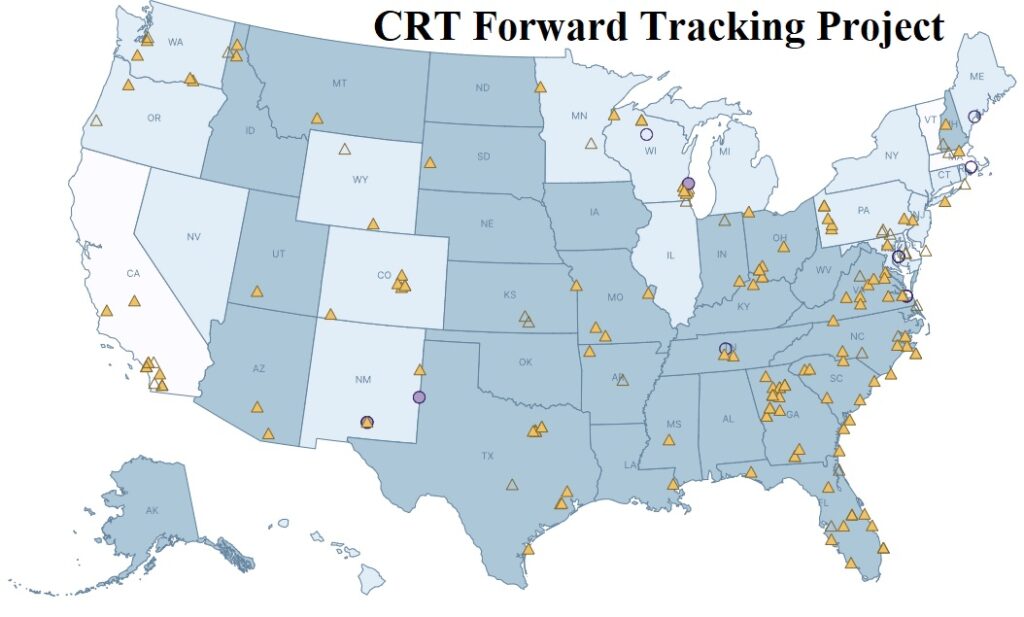

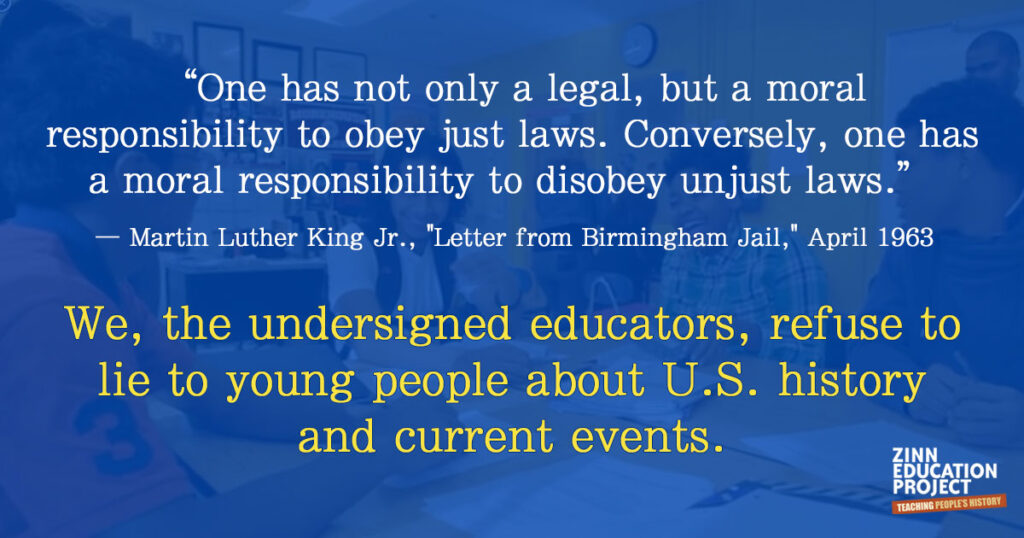

It is important to note at the outset that because CRT scholarship usually takes place at a high level of academic study, it is normally only encountered in graduate programs or law school. Students in grades K-12 are not—let me repeat that, are NOT—studying Critical Race Theory in their classes. An 8th grader doesn’t have the intellectual tools to do a serious analysis of law or construct detailed historical legal analysis. They may be engaging with ideas about equity, diversity, and inclusion, but this is not the same as teaching or doing CRT—a point critics ignore or gloss over in their claims about CRT in schools. As Ohio educators have testified, their engagement with diversity in the classroom is done in an age-appropriate manner using materials vetted by their local school district and which follow Ohio state curriculum standards.

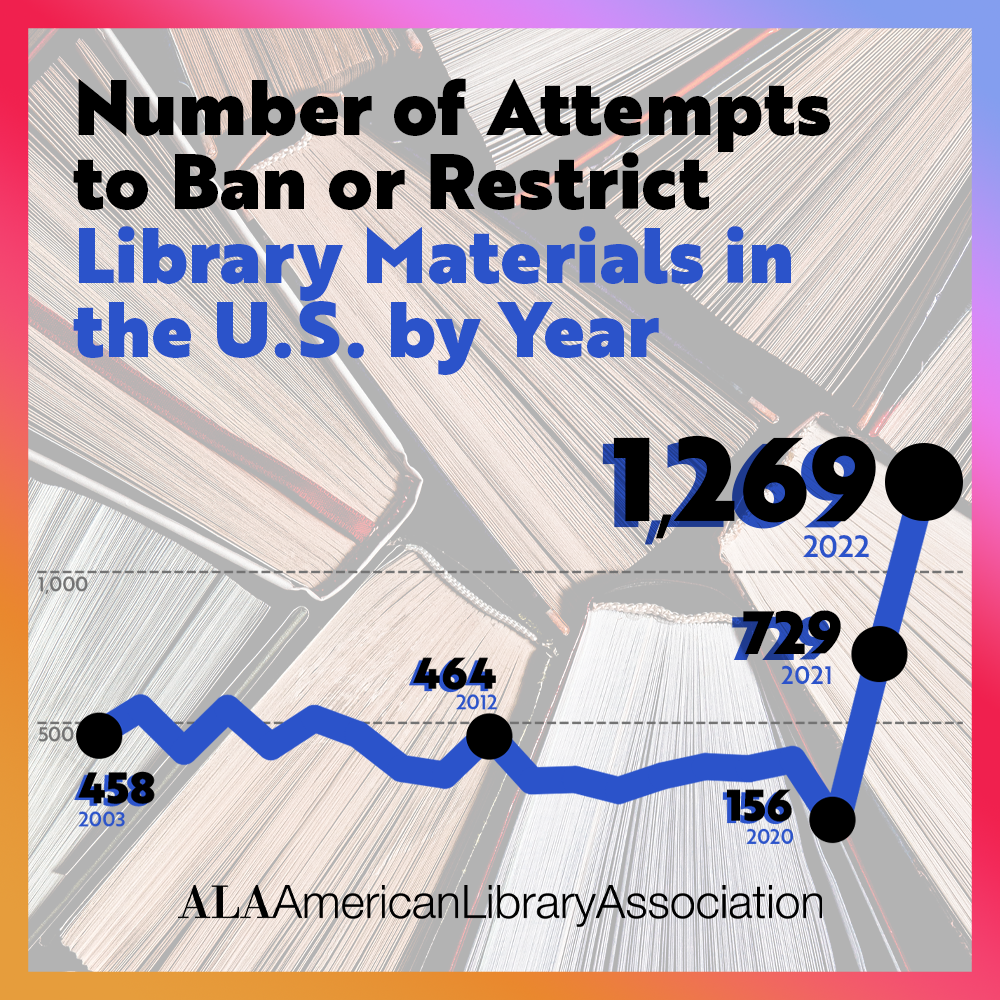

We should also point out that most Ohio legislation attacking social justice education, antiracism and DEI—such as HB 322, 327, 616 or the latest SB 83—don’t actually use the term Critical Race Theory (HB 616 was the exception). But supporters of the bill are quite clear that the target of this legislation is the supposed teaching of CRT and DEI in schools. Here are some common political claims about CRT that frequently show up in public comments:

- Critical Race Theory is a covert attack on core American values, including Christianity, capitalism, individualism, nationalism, the family, and marriage.

- CRT undermines American democracy and seeks to create a Marxist state or promote a Marxist cultural agenda that shames white people and promotes Black victimization.

- Critical Race Theory is itself a form of reverse racism against whites.

- Systemic or structural racism, implicit bias, and white privilege do not exist.

- The US is a colorblind or post-racial society that treats everyone equally (‘MLK Myth’).

- Social/economic progress in the US operates based on meritocracy (individual hard work).

- Anyone critical of Christianity, free market capitalism, and a conservative narrative of US history is an ideological threat, a “domestic enemy,” an “evil” person, and a “poison.”

CRT Basic Readings

If you want to actually learn what Critical Race Theory is, here are two few key texts to begin with.

| Critical Race Theory – An Introduction |

Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement |